Life as God Has It

LIFE AS GOD HAS IT

ζωη(zoe) n. - greek "life". Life in the absolute sense, life as God has it, that which the Father has in Himself, and which He gave to the Incarnate Son to have in Himself (Strongs #2222)

In his adaptation of an Abenaki legend, Joseph Bruchac speaks of the origin of dogs as Great Spirit’s gift to human when He saw we were moving farther from the natural world and therefore farther from Him. Spirit saw that human was in trouble and needed an animal that would sleep inside the shelter, curled up at the foot of the bed. And so came Dog.

I named my dog “Zoe” because it means “life” in Greek. More specifically it means Life as God has it. My dog “Zoe” now as I write this is leaving this other life, life as mortals have it. She’s lying next to me as I write this, as I’ve written so many other pieces, with her beside me through every word. Her white and apricot fur is healthy. It is her winter coat, thick with curls and swirls. The softest fur covers her head, emerges in gold feathers down her ears. I will seek this texture in silk and pussy willows for the rest of my life and remember her. From this memory, the countless others will radiate.

Of Zoe and me running together along the Swannanoa River on the Warren Wilson College property. Of Zoe and me running in the meadows of the Christ School property where I lived for nine years. Of Zoe and me, Zoe and me, Zoe and me. In a life lived, as viewed from the outside, greatly in a solitary way, with Zoe I have never been alone.

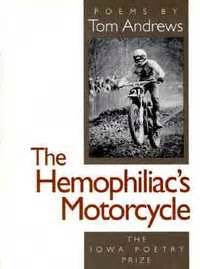

She is the first creature I have raised. I adopted her from the puppy pool at the West Lafayette humane society in Indiana. She was a wedding gift from my fiancé at the time, Tom Andrews, the poet who passed away shortly before the towers were attacked in 2001. I thought she was a boy and named her Hugo at first sight when she peered out from under a child’s little chair placed in the puppy pool as a toy. Her black-rimmed dark eyes reminded me of the seals that swam up to me when I sat by the sea on the Olympic Peninsula. I whispered in her ear on the drive from the humane society, “You’re the dog that’s going to help me raise my child.” My fiancé ended up breaking off our engagement just two weeks later, saying that having a puppy made him realize he didn’t want to have children (he also said I was "taking all the good poems" and that I "blocked his view of God"). I loaded Zoe’s blue cage into the front of the truck I bought off him for one dollar and together we made the drive over the Ohio River and up the Blue Ridge back home, to my mother’s house in Oteen, my life and my heart in pieces.

We rented a house on Riceville Road, the pretty yellow across from the cow pasture with the stream. A parrot lived next door who quickly learned how to mimic me calling her. “Zoe!” the parrot would call out when I did, often causing Zoe to just lie down on the grass confused as to which way to run. For the first three years of her life, I couldn’t have house guests or a boyfriend. She was so rambunctious I expected a lawsuit from my landlady, Grace, for all the times she nearly pushed her over. Upon returning home after a day of teaching teenage criminals at the juvenile center, I’d often weep as she uncontrollable mauled me with kisses. She symbolized how crazy my life had become.

Time passed. Boyfriends arrived and departed. And Zoe calmed down. Living at Christ School in a small two bedroom cottage with limitless room to run, we shared furniture and hours of quiet. She swam in the lake every day in Summer and after school in Fall, when we drove to my parents’ cottage in Canada, she rode on the back of my kayak and we explored Georgian Bay. When she saw something move in the woods on land she’d leap off. I’d follow in my boat and swim from the rocks until she returned, climbed on board and signaled she was ready to move on. I’ve read all of my poems to Zoe. She looks away when the language falls flat and stays focused when the rhythm works. This doesn’t work so well with prose, although some pieces hold her attention better than others. Our lives are intertwined.

When I gave birth to my daughter, Zoe’s mouth at first watered at the sight of the small pink thing I’d laid on the bed next to=2 0me. I’ve only harshly scolded Zoe twice in her life—this time and when she chewed up a long letter from Galway Kinnell, my favorite poet. Once she understood that my daughter Andaluna wasn’t a snack, she took on the role of helping me raise her. She recognized early that, due to my hearing loss, I didn’t always hear my own child cry or whimper when I was writing in another room. With a heavy head pressed onto my lap, she alerted me, and when Andaluna left her toddler bed for a middle-of-the-night trek into the living room to play, Zoe nudged me in my bed. She became my unofficial hearing-ear dog, happy to have a job. She helped my daughter master walking by staying close so the child only had to reach out an arm and Zoe would steady her. And this morning, she would not rise to get off of Andaluna’s bed when I asked if she wanted to go outside. This is how I know we are nearing our end.

From what I can tell, two conversation topics open women up to each other better than any other. The first of these is pregnancy; who among us when pregnant did not become the carrier of “birth stories” from absolute strangers, some of which were gutsy enough to just reach forward and touch our belly as though it was their own. The se cond of this is animal death. Everybody in my life knows that I am losing Zoe. She is the first one they ask about, knowing that the answer to this question is inseparable from the response to the next, how am I doing? Zoe on her journey is creating a coven of love around me, woven of stories of how others have let their beloved four-legged’s go. And like the stories of women who shared when I was pregnant—even the one told me by my waitress at Sagebrush who had the most horrendous pregnancy and birth experience imaginable, a story which terrified me and had me on the phone to my doctor disproportionately to my condition for over a week—these stories are sacred, discomforting and necessary. They help me see that there is a time beyond this moment, a time when Zoe will become a memory, a spirit guide and companion, long after fur and wet nose have vanished. But at this moment, I have only grief and the longing to over-ride the natural course of events and make Zoe live forever.

No matter how full of faith I am, no matter how well I know, for certain, that the spirit world is real and that all being is illusory and flowing and One, I am deeply celebrating my illusion that Zoe an d I are two separate creations, one with a black nose and one with hardly any nose at all to speak of. I am loving that she has paws and I don’t and that when I come home from a day in the world, she wags her tail vociferously, as though I’ve been gone for months. Our illusory separateness is the source of our story. Her dogness gives meaning to my humanness. I’m the one that gives her food. She’s the one that makes sure my daughter and I are safe. In the past when I argued with boyfriends, she’s the one that chose my side and barked at the boy until he left. We’re a union of differences, a partnership of strangers.

I can’t figure out the nature of this grief. From the all the stories I have heard, the depth of grieving humans go to for their pets is admittedly more raw than that they indulge for humans. People pass on. Animals die. People speak of the last days they shared with their animals as “the most beautiful experience of my life” or of the moment they “put him to sleep” as “the hardest thing I’ve ever done.” Superlatives belong to the animal bond. In moving through this sorrow, given my compulsive poetic need to be able to name un-nameable things, I attempt to e xplain it as being a mixture between the love a parent has for a child and that which a child has for a parent. For while I am the one who feeds Zoe, pays her exorbitant vet bills, trims her toenails (if she’ll let me) and provides her with shelter, when it really comes down to who is taking care of whom, I’m the one heavy on the receiving. All the stuff I give is purely material. All the stuff she gives, speechlessly, watchfully, is purely something else, all encompassing.

Possibly feeling a little displaced by all the attention I’ve been giving Zoe and the throes of emotion her leaving spins me into, over dinner the other night my boyfriend brought up a sentence from The Road Less Traveled saying that the love that humans have for animals can’t really be called true love. Because animals don’t have free will and are entirely dependent upon their human, Dr. Peck says. If I were less exhausted from grief and terror of losing Zoe, I might have picked a fight over this one, but rather I joined him in acknowledging that I think there is some truth to that and fed Zoe a bit of chicken from my hand, happy to see her eat anything. But the question pawed at me, if this isn’t true love, what name do I give this inter-species same-sex relationship I have with my dog?

Not quite the love of a parent for a child (remember, I scolded Zoe for thinking my daughter was food) and not quite that of a child for a parent (oh, for just a little of the money I’ve paid my therapist for working through that stuff—Sorry, mom, not you!) and not quite the love of a lover for a lover (I did not pick the fight), the love I have with Zoe has only one more place to go in these comparisons and that is back to the Abenaki story. What else in this universe is very quiet, at times giving and others withholding, ever-present and comforting? Great Spirit sent us our dogs as a way of connecting us to nature and by extension back to Great Spirit himself. In my life of faith and searching, Zoe is my personal love letter from the Creator. And in losing her, I am losing this form of direct contact. And I really don’t want to. And I am comforted by the passage in Mark’s Passion where Jesus—Jesus, whose faith was completely solid with good reason—“became depressed and wept on the ground” during the last supper. No matter what we know or experience of the Spirit, emotion is a necessary process of moving closer to it.

I am writing this on the floor next to Zoe. While I’ve been writing, she has gotten up a couple of times to look out the window, making me wonder if this really the last afternoon-into-evening writing session I will have with her. Truthfully, a part of me hopes it is so I can be free of this fear and move on into grief and loss, emotions I’m considerably more comfortable with, stuff I know how to write. I know how to cope with something that’s already gone. But knowing it is leaving, for me, is the harder task. And possibly this is going to be her last gift to me, this enduring moment of that very emotion I am worst at holding. I have her. She is right her next to me. I am joyful that I can see her breathing and at the same time I am gripped with sorrow that soon I will not. I am living in a three-way mirror of past, present and future, and all three panes show Zoe. Zoe as she was, Zoe as she is, and Zoe as she will be continuously in my memory. They all look the same.

ζωη(zoe) n. - greek "life". Life in the absolute sense, life as God has it, that which the Father has in Himself, and which He gave to the Incarnate Son to have in Himself (Strongs #2222)

In his adaptation of an Abenaki legend, Joseph Bruchac speaks of the origin of dogs as Great Spirit’s gift to human when He saw we were moving farther from the natural world and therefore farther from Him. Spirit saw that human was in trouble and needed an animal that would sleep inside the shelter, curled up at the foot of the bed. And so came Dog.

I named my dog “Zoe” because it means “life” in Greek. More specifically it means Life as God has it. My dog “Zoe” now as I write this is leaving this other life, life as mortals have it. She’s lying next to me as I write this, as I’ve written so many other pieces, with her beside me through every word. Her white and apricot fur is healthy. It is her winter coat, thick with curls and swirls. The softest fur covers her head, emerges in gold feathers down her ears. I will seek this texture in silk and pussy willows for the rest of my life and remember her. From this memory, the countless others will radiate.

Of Zoe and me running together along the Swannanoa River on the Warren Wilson College property. Of Zoe and me running in the meadows of the Christ School property where I lived for nine years. Of Zoe and me, Zoe and me, Zoe and me. In a life lived, as viewed from the outside, greatly in a solitary way, with Zoe I have never been alone.

She is the first creature I have raised. I adopted her from the puppy pool at the West Lafayette humane society in Indiana. She was a wedding gift from my fiancé at the time, Tom Andrews, the poet who passed away shortly before the towers were attacked in 2001. I thought she was a boy and named her Hugo at first sight when she peered out from under a child’s little chair placed in the puppy pool as a toy. Her black-rimmed dark eyes reminded me of the seals that swam up to me when I sat by the sea on the Olympic Peninsula. I whispered in her ear on the drive from the humane society, “You’re the dog that’s going to help me raise my child.” My fiancé ended up breaking off our engagement just two weeks later, saying that having a puppy made him realize he didn’t want to have children (he also said I was "taking all the good poems" and that I "blocked his view of God"). I loaded Zoe’s blue cage into the front of the truck I bought off him for one dollar and together we made the drive over the Ohio River and up the Blue Ridge back home, to my mother’s house in Oteen, my life and my heart in pieces.

We rented a house on Riceville Road, the pretty yellow across from the cow pasture with the stream. A parrot lived next door who quickly learned how to mimic me calling her. “Zoe!” the parrot would call out when I did, often causing Zoe to just lie down on the grass confused as to which way to run. For the first three years of her life, I couldn’t have house guests or a boyfriend. She was so rambunctious I expected a lawsuit from my landlady, Grace, for all the times she nearly pushed her over. Upon returning home after a day of teaching teenage criminals at the juvenile center, I’d often weep as she uncontrollable mauled me with kisses. She symbolized how crazy my life had become.

Time passed. Boyfriends arrived and departed. And Zoe calmed down. Living at Christ School in a small two bedroom cottage with limitless room to run, we shared furniture and hours of quiet. She swam in the lake every day in Summer and after school in Fall, when we drove to my parents’ cottage in Canada, she rode on the back of my kayak and we explored Georgian Bay. When she saw something move in the woods on land she’d leap off. I’d follow in my boat and swim from the rocks until she returned, climbed on board and signaled she was ready to move on. I’ve read all of my poems to Zoe. She looks away when the language falls flat and stays focused when the rhythm works. This doesn’t work so well with prose, although some pieces hold her attention better than others. Our lives are intertwined.

When I gave birth to my daughter, Zoe’s mouth at first watered at the sight of the small pink thing I’d laid on the bed next to=2 0me. I’ve only harshly scolded Zoe twice in her life—this time and when she chewed up a long letter from Galway Kinnell, my favorite poet. Once she understood that my daughter Andaluna wasn’t a snack, she took on the role of helping me raise her. She recognized early that, due to my hearing loss, I didn’t always hear my own child cry or whimper when I was writing in another room. With a heavy head pressed onto my lap, she alerted me, and when Andaluna left her toddler bed for a middle-of-the-night trek into the living room to play, Zoe nudged me in my bed. She became my unofficial hearing-ear dog, happy to have a job. She helped my daughter master walking by staying close so the child only had to reach out an arm and Zoe would steady her. And this morning, she would not rise to get off of Andaluna’s bed when I asked if she wanted to go outside. This is how I know we are nearing our end.

From what I can tell, two conversation topics open women up to each other better than any other. The first of these is pregnancy; who among us when pregnant did not become the carrier of “birth stories” from absolute strangers, some of which were gutsy enough to just reach forward and touch our belly as though it was their own. The se cond of this is animal death. Everybody in my life knows that I am losing Zoe. She is the first one they ask about, knowing that the answer to this question is inseparable from the response to the next, how am I doing? Zoe on her journey is creating a coven of love around me, woven of stories of how others have let their beloved four-legged’s go. And like the stories of women who shared when I was pregnant—even the one told me by my waitress at Sagebrush who had the most horrendous pregnancy and birth experience imaginable, a story which terrified me and had me on the phone to my doctor disproportionately to my condition for over a week—these stories are sacred, discomforting and necessary. They help me see that there is a time beyond this moment, a time when Zoe will become a memory, a spirit guide and companion, long after fur and wet nose have vanished. But at this moment, I have only grief and the longing to over-ride the natural course of events and make Zoe live forever.

No matter how full of faith I am, no matter how well I know, for certain, that the spirit world is real and that all being is illusory and flowing and One, I am deeply celebrating my illusion that Zoe an d I are two separate creations, one with a black nose and one with hardly any nose at all to speak of. I am loving that she has paws and I don’t and that when I come home from a day in the world, she wags her tail vociferously, as though I’ve been gone for months. Our illusory separateness is the source of our story. Her dogness gives meaning to my humanness. I’m the one that gives her food. She’s the one that makes sure my daughter and I are safe. In the past when I argued with boyfriends, she’s the one that chose my side and barked at the boy until he left. We’re a union of differences, a partnership of strangers.

I can’t figure out the nature of this grief. From the all the stories I have heard, the depth of grieving humans go to for their pets is admittedly more raw than that they indulge for humans. People pass on. Animals die. People speak of the last days they shared with their animals as “the most beautiful experience of my life” or of the moment they “put him to sleep” as “the hardest thing I’ve ever done.” Superlatives belong to the animal bond. In moving through this sorrow, given my compulsive poetic need to be able to name un-nameable things, I attempt to e xplain it as being a mixture between the love a parent has for a child and that which a child has for a parent. For while I am the one who feeds Zoe, pays her exorbitant vet bills, trims her toenails (if she’ll let me) and provides her with shelter, when it really comes down to who is taking care of whom, I’m the one heavy on the receiving. All the stuff I give is purely material. All the stuff she gives, speechlessly, watchfully, is purely something else, all encompassing.

Possibly feeling a little displaced by all the attention I’ve been giving Zoe and the throes of emotion her leaving spins me into, over dinner the other night my boyfriend brought up a sentence from The Road Less Traveled saying that the love that humans have for animals can’t really be called true love. Because animals don’t have free will and are entirely dependent upon their human, Dr. Peck says. If I were less exhausted from grief and terror of losing Zoe, I might have picked a fight over this one, but rather I joined him in acknowledging that I think there is some truth to that and fed Zoe a bit of chicken from my hand, happy to see her eat anything. But the question pawed at me, if this isn’t true love, what name do I give this inter-species same-sex relationship I have with my dog?

Not quite the love of a parent for a child (remember, I scolded Zoe for thinking my daughter was food) and not quite that of a child for a parent (oh, for just a little of the money I’ve paid my therapist for working through that stuff—Sorry, mom, not you!) and not quite the love of a lover for a lover (I did not pick the fight), the love I have with Zoe has only one more place to go in these comparisons and that is back to the Abenaki story. What else in this universe is very quiet, at times giving and others withholding, ever-present and comforting? Great Spirit sent us our dogs as a way of connecting us to nature and by extension back to Great Spirit himself. In my life of faith and searching, Zoe is my personal love letter from the Creator. And in losing her, I am losing this form of direct contact. And I really don’t want to. And I am comforted by the passage in Mark’s Passion where Jesus—Jesus, whose faith was completely solid with good reason—“became depressed and wept on the ground” during the last supper. No matter what we know or experience of the Spirit, emotion is a necessary process of moving closer to it.

I am writing this on the floor next to Zoe. While I’ve been writing, she has gotten up a couple of times to look out the window, making me wonder if this really the last afternoon-into-evening writing session I will have with her. Truthfully, a part of me hopes it is so I can be free of this fear and move on into grief and loss, emotions I’m considerably more comfortable with, stuff I know how to write. I know how to cope with something that’s already gone. But knowing it is leaving, for me, is the harder task. And possibly this is going to be her last gift to me, this enduring moment of that very emotion I am worst at holding. I have her. She is right her next to me. I am joyful that I can see her breathing and at the same time I am gripped with sorrow that soon I will not. I am living in a three-way mirror of past, present and future, and all three panes show Zoe. Zoe as she was, Zoe as she is, and Zoe as she will be continuously in my memory. They all look the same.

Comments