The Suicide Push

In the two days that presented us with celebrity suicides, I have been quiet. I saw the posts and acknowledged the tragedies. The fame and fortune of both Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain--and also the charm each possessed--nestled in with the personal notes from friends and relatives to script fragments of stories together that will never be whole. Like the poems of Sappho salvaged from ancient ruins, this is all we are left with. I had nothing to say, and I'm often one who can say something.

My silence indicated to me that it wasn't a reflection of not feeling anything or not having anything to contribute to the communal grieving and raising of awareness. It indicated that there was a block in me. I was blocking the grief and even the witness.

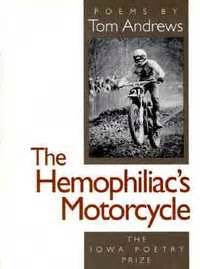

Back in the 1990s, I was engaged to Tom Andrews, the beautiful poet. The story I tell most often about this fait-incomplit of an engagement is that at his memorial service a friend of his turned around in his chair and asked me if I was "one of the fiancées." Sure enough, there were five of us there, including the one on whose wedding day Tom had slipped into a coma that would turn into his death from a rare blood disease. Tom was a hemophiliac, but he did not die of hemophilia, a fact that rather fit tidily in his own self-recognized narrative of having been the one that beat the odds repeatedly, and this narrative he celebrates in the collection The Hemophiliac's Motorcycle and later in Random Symmetries and stunning medical narrative, The Codeine Diary. He had been one of the 2% of people who had received blood transfusions and survived when the blood supply was discovered to carry HIV.

When his best friend, who was going to be Tom's best man perhaps at all his almost-weddings, called to tell me he had died, the first thought through my mind was "he finally did it." I didn't mean he'd finally had a fatal bleed. I meant he'd finally succeeded at suicide. I don't tell the story of Tom's suicide attempt because the "five fiancées" story is such a winner, complete with all of us being seated together at the reception and his father's commenting "my son had such great taste in women." That story is a killer. It's the other story, the one I don't tell, that kills me.

The story I can hardly bring myself to tell is the one of how he broke off our engagement. Abruptly. We had bought a house together and had just adopted a puppy. We had rented a villa in Tuscany for the honeymoon, and Tom had bought me a grand piano as a wedding present. There were pieces in place that looked to be a wonderful picture. One afternoon I was listing off prices for various flooring options for the new house when he told me blankly, "I can't do it."

"Parquet?" I asked. "Well, we can go with the berber."

"Laura, I'm not talking about flooring."

I didn't fight. I dislike scenes and have long known I'm far too good at them and that my words can eviscerate when set loose with anger. I told him I'd take the puppy, and I loaded up my truck with the items I'd moved into our house months before. He was resolved that he didn't want to marry me. I was resolved that I didn't want to convince him. If he changed his mind, he'd call me back to him after a time. Why risk ruining everything with words now? I drove east over the Ohio, stoppping every few hours to let myself and the puppy pee.

I found out weeks later from our best man that the day I left, Tom had driven out to the new house and attached a hose to the exhaust pipe of his car, sealed it with duct-tape then fed it through a slightly opened window and duct-taped all open air out. A neighbor had come by to meet the "new couple" who'd bought the place. Tom was unconscious and rushed to the hospital then admitted into psychiatric care.

I had been hating him the whole time, telling myself with every day that he didn't call me that Wow I really should have let him have it.

After hearing what had happened, I wondered if I had expressed my feelings, if maybe I'd been harsh, if maybe I had done what I tried hard not to do and said something that had driven him over the edge.

Two years later he was seated next to me on an airplane, a 6 a.m. flight from Cincinatti to Asheville. I was returning from a visit with friends in L.A. He was arriving to teach creative writing at the school where we'd met. The chances of our being placed side by side astonished us both enough to over-ride any awkwardness. I felt his arm's strength through his leather jacket. He'd put on weight. He was happy, in love with a woman in Athens, Greece. They were engaged.

We met for a walk with "our" now full-grown puppy, Zoe. He told me that he had gone off his medication when we were together because "I was finally happy." He had told me shortly after we'd met that he was a "citizen of Prozac nation" and was on other anti-depressants. He now told me he'd gone off them months before breaking up with me--around the time we visited friends in frozen Minneapolis I thought as I pieced the narrative together, remembering I'd driven home in Spring. In short, he said, I hadn't stood a chance against the depression that was swallowing him. He was saying it wasn't me.

A few months later I got the call from our best man: he was dead. The blood disease he must not have known was emerging when we walked had taken him. It was his second death, I felt. If not his third, if you count the near-miss on the infected blood supply. I thought about how maybe he had willed his own death, having failed at suicide years before. I caught myself. He was dead. I had to grieve him, not understand him. Months later at his memorial, I was surrounded by his other fiancées. Again, I had to grieve him, not understand him.

He is the boyfriend my mom and step-father agree was the One. Charming, brilliant, hilarious, kind, blessed with excellent social skills and capable of long, meandering, insightful conversations. I remind them: Bipolar. Off-meds.

What would have been enough, I wonder when I allow myself to wonder.

He was smiling and waving at me as I drove away. Smiling and waving. He was pushing me out of his life so he could end it. Smiling and waving. Making room. And rather than being able to tell me and express his fear of what he might do to himself, the suicide was already in control. The suicide had seized him weeks or months before. It saw me as its enemy, something in the way. Maybe before the new house or the puppy, and he had been fighting back against it with these tokens of a life we'd create together. But he had not won. Smiling and waving.

The suicide was already there. In our lives. In our bed. In our story.

My silence at the deaths of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain are because of this. I think about the people surrounding them. I think about the urgency with which we are told to reach out, to support, to be there for each other and know from my experience that that wasn't what it was about. The scariest thing in the whole world to me is that there wasn't a single ask. Not a single request that I sit and listen. No request for help and no sign of suicide that would happen that same day. There was a wedding gown, a puppy, a villa in Tuscany. These were the signs of suicide for Tom.

This is my story of Tom.

You can see why the other story I often tell is the favored one.

This one is just too terrifying.

Comments

David H

Babo